the first time she saw a performance of The Magic Flute.

The electrifying moment came when the Queen of the Night launched intoSublime moments, she argues, are points where significant forms, in

her aria. I sat bolt-upright on the edge of the seat, and must have

held my breath for the entire duration. My heart ached and tears

welled up in my eyes. Her voice rang through me everywhere as though I

had dematerialized into an exquisitely sensitive ethereal being that

filled the auditorium. There was intense excitement, but also

something supremely joyful and serene. No words can capture that

charged moment but that I was in the presence of the

sublime.

active engagement, create something akin to love.

"Love" is an overused and abused word, and hence thoroughly inadequate

to describe the rich panoply of feelings that make up the aesthetic

experience. Nevertheless, for those who have been fortunate enough to

have experienced love in the sublime, it is indeed not dissimilar. It

too, is a feeling of heightened awareness of being connected, not only

to the loved one, but to everything else by sympathetic transference

(of both sameness and contrast). The lover is indeed in love with the

whole world. The loved one becomes a sign through which everything

else, even the most ordinary and mundane, is known and loved afresh:

the whole world takes on a new significance.”

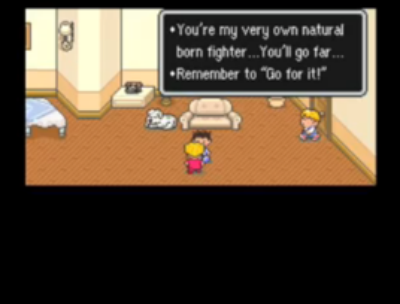

The last time I played through Earthbound a line early in the game

jumped out at me. Before Ness starts out on his big adventure his

mother gives him some words of encouragement, including the advice:

“Remember to ‘Go for it!’” I was stuck by the profound absurdity of

this statement. Those quotation marks add so much. By including them

Ness’s mother acknowledges the emptiness of her platitude and further

cheapens the advice by not simply telling Ness to “go for it”

(whatever “it” is) but not to forget to follow the hollow cliché. In

five words we have a critique on the worthlessness of generic sanguine

encouragement far more scathing than any photoshop of a “teamwork”

encouragement poster ever was. But at the same time she is so sincere,

so genuine with her support, that the sentence twists back on itself

into an ouroboros of quiet, deep hilarity. Finally getting the joke,

and the realization of what masterful writing this was, was a moment

of sublimity.

Despite playing the game consistently since its 1995 debut it still

took more than a dozen playthroughs before the "Go for It!" line

distinguished itself for me. Earthbound is the only game where each

repetition brings new revelation. It is a mine which never depletes,

and with each unearthing produces a new and precious gem. There is so

much than endears me to this game that goes beyond the usually

ascribed appeal of wh-whackyness! and “It’s an RPG set in modern times

with like baseball bats instead of swords and stuff!” Director

Shigesato Itoi’s direct but rich and subtle script is only the

beginning.

I marvel at how the graphics which seemed so primitive in ’95 have

only become more timeless and iconic as the game ages; at how the

music is affecting with both melodic and ambient tracks, both layered

with a seemingly endless amount of samples and references; at the

sound that a bicycle makes riding through a swamp.

While all these are well documented details adored by many players,

Earthbound offers personal revelations as well. I was 14 when I first

played the game, and though I first dismissed it as childish and

simple, it lodged itself into my brain. One day I surprised myself by

unconsciously humming the theme to Onett. I was impressed that this

game I had found so distasteful had managed to imprint on me so

strongly. One moment in particular captivated my memory: the trumpet

player who stands on the cliff overlooking the sea playing Dvorak's

Symphony No. 9, Movement 2. Something about that haunting melody

overlaid with the Onett theme sparked a powerful sense of nostalgia,

despite having only played the game a few weeks earlier. This was the

first sublime moment and because of it I returned to Earthbound with

an open mind and an eager heart.

Earthbound has the unique and special property to engender nostalgia.

Both for itself and within itself. To a large degree the plot is about

recovering sweet memories, and there’s nostalgic quality in nearly

every location. A sense of both goodwill and impending loss. The

allure of Earthbound’s nostalgia is so strong that not even the game’s

primary antagonist is immune to its allure.

For several years after when I encountered a particularly beautiful or

seductive place in nature I would call the spot one of “My

Sanctuaries” after the gentle places of power in the game. Such was

the strength of association between Earthbound’s special sense of

nostalgia and real life discovery, beauty, and fleeting tranquility.

Since then I’ve made other happy discoveries within Earthbound’s mise

en scene (for lack of a better term). These include the recognition

that as you move through Onett to Fourside you also travel through a

year from late summer to the hight of spring. Or that the noise in the

background during Poo’s trail is the sound of Om. Unverifiable

interpretations these may be, but for me they enrich and personalize

the experience.

Earthbound is a game constructed out of small sublime moments. Or as

the game itself says over a warming cup of tea, “like a great

tapestry, vertical and horizontal threads have met and become

intertwined, creating a huge, beautiful image.”

Divine as these moments are, none come close to the definition of

sublimity as love. No, that moment comes, as it should, at the end.

The main through-line of the game is that Ness is visiting his My

Sanctuary locations to gain enough strength to defeat an evil alien

who has enslaved the earth in the future. At each location Ness

receives part of a song know as “Eight Melodies.” It’s a beautiful

song, though until it’s completed is filled with a considerable amount

of discord. During the final credits a expanded version called “Smiles

and Tears” plays while images from throughout the game play in the

background (there’s that nostalgic element popping up again). “Smiles

and Tears” is a moving and profound end to the game. The perfect cap

to an amazing ending. However, very very faintly, just as the music

swells to a climax, a voice whispers “I miss you.” It’s so faint that

many people miss it entirely. I completed the game at least ten times

without hearing it myself. After learning about the line on the

internet, and that it was Shigesato Itoi’s voice no less, I made sure

to listen carefully the next time.

One of the main questions in the 'Are Games Art?' debate is if a video

game can make a player cry. Most often this is couched in terms of

narrative, that a game could tell such a moving plot with such

compelling characters that the player would be moved to tears. While

I’ve been moved by games narratives before (Mother 3 and Shadow of the

Colossus spring to mind) I’ve never been close to crying.

"I miss you."

When I heard those words for the first time I felt such a powerful

upsweeping of emotion that I had to blink and wipe the back of my hand

across my eyes. It may not have helped. People have speculated what

this whispered message means. Is it Ness professing is desire for

Paula? Is it a reference to Mother 3? To me it couldn't be more clear.

Here, this game which I have spent so much time with, have discovered

so much about, which has influenced who I am and how I see the world,

and which knows me by name, was telling me personally and singularly

that it regretted that our time together was over. It was confirmation

of a profound connection between me: player, audience, person and a

immaterial collection of data and ideas put together by a man half the

world away who I had never met. It’s hard to express the depth of my

feelings. I can only echo the sentiment of Dr. Ho: no words can

capture the moment I was in the presence of the sublime.

“The creation of significant form is an act of communion, of love"The importance of EarthBound isn’t found in its contributions to the

between artist and nature, between artist and amateur, between amateur

and nature. It is nature presenting nature to herself through us who

are all of the same cloth, to reaffirm and celebrate that universal

wholeness that is both the source and repository of all

creation.”

development of the medium, but to the development of actual human

beings who played it during their formative years." -Michel

McBride-Charpentier

No comments:

Post a Comment