Sunday, August 17, 2008

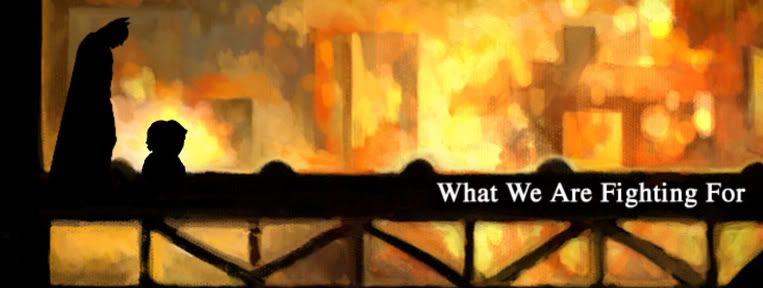

During the credits for The Dark Knight, we sat still with no desire to join the throngs of moviegoers leaving the theater. No one said much. There wasn't much to say, and we were tuned enough to understand that.

Then Jess, meaning well, began to compliment the story. "It's so literary," she said.

Lauren stood up. "Whoa," she said, cutting Jess off, "Hold on," adding some sort of epithet in reference to Jess' promiscuity - "slut," "whore," etc.

Lauren straddled Jess in her seat and grabbed her like she was going to drop her from a fire escape.

"Don't you dare," Lauren said. "This is a glowing example of the film medium."

I was in a receptive state, a feeling very close to prayer or post-coitus. Both happy and sad, I was looking for something that made sense to me.

Hideo Kojima said that Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty was his attempt to tell a story that could only be told in the medium that he used. The player could indeed trigger events and conversations through optional interactions, but was this material "story" or were they just examples of hypertext; Easter eggs?

Is it really possible to tell a story in one medium that could not be told in another?

The Dark Knight could have been a novel, I guess, at the forfeit of subtlety. I guess you could give a description of The Joker's joy ride - that reprieve from the violence and the maniacal laughter, a moment of serene satisfaction, a devil in heaven - but, God, why not just SEE IT? Besides everything, half of the movie is a series of parallel actions that would be too clumsy to render in text.

Interestingly enough, Metal Gear Solid 2 is not the video game that I consider to be medium's best example of storytelling. For a while, it was Silent Hill 2. It featured Easter egg-style deposits of information, as well, but as far as I know, it's the only game that actually interprets the way in which you play the game to decide the ending - even if you didn't mean to come across as suicidal when you decided to examine the knife intently and drag your wounded ass around without using any Health Drinks for six hours.

We haven't gotten too much closer. Silent Hill 4 tried to reinvent the series like Resident Evil 4 did and fell flat on its face, becoming neither a great game nor a fantastic experience. Metal Gear Solid 4, while dazzling, is essentially an interactive five-part HBO special event.

But how could it be that video games haven't reached their full potential? Aren't the graphics good enough yet? Aren't DVDs and Blu-Ray discs big enough to contain all of that hard work and money and the products thereof? Aren't they real enough? Aren't they cinematic enough?

Aren't they unlike video games enough?

Portal does not present you with a cut scene detailing its world's rich history or the main character's back story, or a romantic other - at least, not in the typical sense. What you see is what you get. The rest is for you to figure out. What is the point, then? Why run around and shoot your gun? Well, what else are you going to do when someone gives you a gun and a series of hallways to run through?

A game makes us believe that, in its world, there are parties with differing interests: an architect, a benefactor, an obstacle. In Portal, they're all one in the same: GLaDOS. But the illusion of conflicting interests, overcoming obstacles to meet an end, is true in all video games. Portal knows this.

Rather than just looking at other video games for inspiration, Portal looked at the medium itself. The question was not, "What gimmicks can we copy and expand on?" but, "What do we have here, and what can we do with it?" Of course, I know that Portal was made with Half-Life 2's Source engine, but the fact that such a revolutionary simulation of real-world physics could be taken and turned on its head (as the player does with Aperture Science's portal gun) is a testament to the sense of discovery inherent in the game.

Portal is brilliant because it does not strive to be anything other than what it is. In doing so, it lights a fire under the old cliches, reminding us why they were such good ideas to begin with. The cliches become archetypes.

There's something I heard Carl Sagan say once: "If you want to make an apple pie from scratch, you must first create the universe."

Braid is that apple pie. It is scrumptious and terrifying.

Like Portal, Braid is a video game about video games and, by extension, everything.

When I say it's about video games, I don't just mean the medium. I mean video games; specifically, Super Mario Bros. It's plain to see: an adorable man-child hero (Tim), stubby bipeds vulnerable to blows on the head, princessless castles at the ends of stages, and there's even a Donkey Kong effigy in World 3. Braid is to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead as Super Mario Bros. is to Hamlet.

Think about that: we have finally reached the point in history where Super Mario Bros. is something to be referenced, revered and dissected. Rejoice. Or weep. Whichever.

When you defeat Bowser at the end of the first seven worlds in Super Mario Bros. and Mario walks off to the right to presumably find Princess Toadstool, a mushroom-headed little man greets him and tells him something that has become a joke among nerds, as well as a slogan on a T-shirt that I own:

"Thank you Mario! But our Princess is in another castle."

Braid investigates the seriousness of this statement. Indeed, if Tom Stoppard had made Braid and needed a quote for the title, he might have called it "But Our Princess Is in Another Castle".

It should be known that Braid is its own game. Again, like Portal, it is what it is - an ingenious series of challenges set one after the other, all hinging on a clever mechanic. In Braid, it is the control over the flow of time. And because time is under your control, the number of times any challenge can be attempted is limitless; death and the Game Over screen is nonexistent. Time control is such a seamless part of the game, as natural and running and jumping, you might begin to wish that EVERY game worked the same way. Braid should be remembered for this alone.

Through diaries lain out in the cloudy lobby of each world, we learn that Tim lost the princess - "This happened because Tim made a mistake." However, since gaining control over time, Tim refuses to let his mistakes stick, and has vowed to fix everything in his control.

However, Tim's control starts to slip away. As the game progresses, the player comes across creatures and objects that are unaffected by Tim's powers, and obstacles he has to stretch his abilities to their limit to overcome by creating parallel timelines and imbuing his ring with chronological energies. The challenges become more and more oppressive, just like any video game.

But what if the given difficulty curve of a game increased indefinitely? What if the challenges suddenly became humanly impossible?

Tim can change the course of his actions and the actions of those around him, but he can't change their minds.

Tim doesn't just fail to rescue the princess - that would just be mean, to make failure the only outcome. No. Tim fails in his assumption that the princess ever even wanted to be rescued. He fails in his assumption that he can control the outcome of everything. He fails in his assumption that he even deserves a tangible reward for his efforts.

Take a look at Braid's web site. The game has no manual or box to summarize its content, so the web site is pretty much it.

http://braid-game.com

The site doesn't mention any princess. The description at the download screen doesn't mention the princess. Only the enigmatic diaries convinced me that the princess' rescue was my main objective.

According to the web site, my main objective was to solve puzzles.

The fact is, Tim never assumed anything. Tim doesn't even say a word in the whole game. It was me. Only me. I am the one who wanted to save the princess. I am the one who wanted my efforts rewarded. I am the one who wanted my actions to count for something outside of myself.

I am the one who missed the point.

Old games had terse and disappointing endings all the time - a single screen that said, "Thank you for playing." And then you're brought back to the title screen, to start again, like you're just supposed to keep going.

Tim can do nothing but keep going. There are no staff rolls or developer insignias to get in his way. It never ends. Nothing ever ends.

What else can you do but keep going?

Lawrence told me that The Dark Knight is a tale of hopelessness. Bending the rules is the only way to overcome the odds, and no good deed goes unpunished. The only way to validate the hope of the people is to lie to them. Alfred even denies Bruce closure by burning Rachel's letter, in order to fuel Batman's righteous anger.

"But at least he's alive!" I said to him somewhat desperately.

Are results the most important thing? How well or how fast or success or failure? To experience the doing is the essence of living, isn't it?

I don't know when it's going to end, if it ever will. Even if there's no princess, as long as I don't know whether I'm right or wrong, all I can do is continue the fight.

No comments:

Post a Comment