When I was a kid, The Illusion of Gaia took me a long time to play through. I had lousy reflexes and I was too dumb to solve the puzzles very quickly. The abandoned continent of Mu, for example, took something like a month for me to get through.

This time, though, it just breezed by - it took me a single evening to reach Mu, and another to reach the floating village of Watermia. I can't believe I never noticed how fast-paced the game is. You're constantly getting thrown into crazier situations, with very little rest between each new challenge. I'm starting to think that my beloved Chrono Trigger took a tip from Gaia in that department.

Unlike its spiritual predecessor Soul Blazer, in which you can travel between all areas of the game at practically any time, Gaia is incredibly linear. After triggering certain events, you're carried further into the story to the point that you can't turn back. Me, I've always appreciated a bit of linearity. It ensures progress, and it keeps the game from getting stuck in a rut.

Every new location you reach is special because you know you won't get a chance to explore it again. The game feels like an adventure novel - the climax of each chapter gives way to anticipation for the new sights and sensations to come. I asked my friend Lawrence what it is that's missing from new games in comparison to something like Gaia. "Mystery," he said.

Gaia's world is a strange one indeed - a mish-mash of enigmatic and historically important locations, crunched together to negate most of the actual distance between them in space and time. Freejia and the Diamond Coast, obviously a play on the Ivory Coast, are likely a diarama verion of apartheid-era South Africa. Euro is a singular, vague representation of a bustling mid-Rennaiance Romantic city. Other locations, like the Nazca Plains, the Great Wall of China, Ankor Wat and the Great Pyramid, speak for themselves.

Many of the cultures are rendered with an equal amount of respect, despite the rampant use of artistic license in their depiction (though there is a fisherman in the Vietnam-ish village of Watermia who knocks up his wife then goes on to gamble away his life in a game of chance... but there are nice fishermen, too). It was neat to be privy to such knowledge as a kid, though really, Gaia taught me about as much about the Angkor Wat as Parasite Eve taught me about mitochondria, which is not much.

Soul Blazer's story of a world being restored from the nothingness, while grand, was less effecting to me than Gaia. Like all great stories, Gaia's is huge and at once personal - a young school boy leaves his childhood behind to become the harbinger of a new age of civilization. Along the way, many great and terrible things befall him and his friends, and he must forego his innocence for the good of the world.

At the game's end, Will reaches the top of the Tower of Babel - the Old Testament tower essentially built as a challenge to God - defeats the heavenly invader that threatens to erase humanity and all of its feats, and gains the comfort of knowing that people will continue to thrive, taming the demons of their past and continuing to aspire to greatness.

The Japanese have been tapping the well of Judeo-Christian lore to pad out their fiction for a long time. Gaia's use of biblical imagery, though, is rare in that it seems to be used to an end outside of empty symbolism.

In the story of the Tower of Babel, the tower is a symbol of human avarice. God changes the tongues of all those who built the tower, so that they each speak in languages that others can't understand (arguably "babble" is derived from "Babel" - huh!). This explains how different languages arose from a common people, and why those people chose to remain separated from each other in different tribes.

In Gaia, though, the tower is not struck down by a divine power. Instead, the divine power (a meteor controlled by "Dark Gaia," probably inspired by the fallen star Wormwood from Revelations) is struck down by Will - a boy who has traveled the world and delved deep into the hearts of all cultures. Will, rather than being a symbol of human pride and territorial cowardice, is a culmination of all of the knowledge and achievements of human civilization. He doesn't stand for any one tribe, but all of humanity.

From the top of the tower, Will sees, not just the world, but human history stretched before him - a history of fantastic feats, not by god, but by man. Even throughout the game, all of the awe-inspiring ruins of the past, which may have been built in the names of gods, were built with the hands of people. Gods, even when they do appear, are relegated to hidden, single-screen save rooms, floating in obscurity like Zordon.

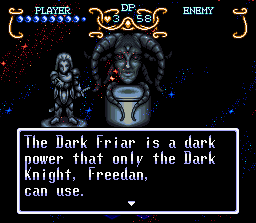

One of the strangest relationships in the game is that between our hero Will and the goddess Gaia. You first encounter the goddess on the roof of Will's school in South Cape, on the other side of an ethereal door into Dark Space. Approaching her reveals that you're the chosen one or some such, and then she offers to save your game. Will has no qualms with this. Is this not the first time he's met Gaia? Why is Will her earthly emissary? Just what kind of goddess is she, anyway? Unlike the Master in Soul Blazer, Gaia does not appear to be the beloved caretaker of the world. Hell, I don't think anyone in the game acknowledges Gaia at all. Could it be that the age of exploration has also brought upon the age of atheism?

Or it could be that Gaia is actually Will's own "personal" god, an embodiment of the courage and power he needed to help him fulfill his destiny. With the defeat of Dark Gaia, Will takes back his responsibility and recognizes the power inherent in himself. Maybe THAT'S the illusion of Gaia.

It's hard to believe that the game is capable of any statements about the relationship between man and god when you look at the writing. It barely even reaches the level of mechanically elegant simplicity exhibited in Soul Blazer. I'm not sure if it's just because of the script's translation, but some of the dialogue ranges from laughable melodrama to outright nonsense. Will's internal monologues are sometimes in past tense, sometimes in present tense, sometimes in first person, sometimes in third person. Sometimes the subject and the object of certain sentences just aren't clear. Will's friend Eric says to no one in particular, "Don't tell anyone," when he really means, "I won't tell anyone."

Such fumbling translations were commonplace back then, but after seeing how far we've come (especially after comparing the script of 1997's Final Fantasy Tactics with the vastly improved script of the 2007 remake), it's so disappointing to see the more successful tenets of story-telling from the 16-bit era being hampered by a standard of mediocre writing that never should have occurred. Old games told stories in a way that new games have overlooked, maybe because developers assumed that simplistic story-telling was a byproduct of primitive technology. Subtlety and even visual coherence became much less imporant when we started jamming dazzling FMV cinemas into our games - not to mention load times, inconsistent voice acting, and drawn-out battle animations - just because current mediums have the space for it.

ANYWAY, pangs of insight do happen to shine through during certain moments of the game, though typically anything poignant is more a result of the situations depicted rather than the writing. At one point, Will has to play a song on his flute to restore the memories of his amnesiatic friend Lance. However, in doing so, all the other characters in the room suddenly become incredibly nostalgic, homesick and sad. Later on the princess Kara, who ran away from her "prison of silk and gold", learns that home is where the heart is, saying, "When I'm far away, I feel close to it. When I'm close, I feel far away." And these are all 14 and 15 year old kids. I guess I just have a thing for sad children.

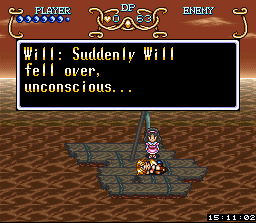

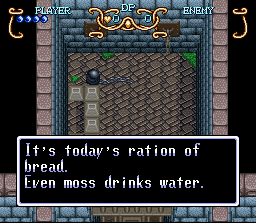

But sometimes the game misses golden opportunities to capitalize on incredibly dramatic scenarios. In order to get off of the continent of Mu, Will and friends have to travel through an ancient underground tunnel - a grueling hike that ultimately takes a month to complete. It's probably one of the most harrowing experiences that the entire group goes through together, bereft of sunlight or any sort of sustenance aside from dirty water and cave mushrooms.

Rather than allowing you to experience any of it - except for one part where you have to walk over to the other side of the screen and grab a mushroom - the scenario mostly just plays out through dialogue, flashing forward periodically, and it doesn't last for more than two or three minutes. The tunnel scenario is much different from one great sequence earlier in the game, in which Will and Kara are stuck on a piece of wreckage in the middle of the sea. At least you can catch fish in that part.

I can't believe I forgot how good the game looks. The environments are colorful and detailed, the monsters are strange and scary, the animation of the wind blowing through Will's hair is so visually impressive that it's emblematic of the game entire, and the music that accompanies them all is always affecting, if a bit bombastic.

I think the one thing that keeps Gaia from being remembered for its aesthetic contributions are the graphics for the NPCs. They're just so plain and static, like 2D Playmobil figures. It's also really weird to think that cute characters like Kara live in the same world as some of the awful monsters you have to fight.

Come to think of it, the graphical discrepancy provides an interesting dichotomy: the world of the plain and placid NPCs and the world of the frighteningly detailed monsters.

But then that still doesn't explain why the laboriously animated Will looks so weird standing next to his incredibly boring-looking friends. It's more likely that some of the artists were way lazier than the others.

That explains the shortcomings of so many great works - some guy just did not do his job as well as everyone else.

When I was a kid, I liked Gaia well enough, but it was always "that adventure game that isn't Zelda". This time, I was finally able to enjoy it, not in how it compared to other games I liked, but for what it was - a strange and exciting tale of a boy and his world reaching their potential. How come it took so long for me to appreciate it? Could it be from the insight I have gleaned from my college education in semiotics, symbology and stage direction? Or am I just crazy with nostalgia? I guess that depends on how deeply you care to look at it.

FUN FACT: The first name to appear in the credits was the woman who wrote the story, Mariko Ohara. She is a science fiction writer, and was the president of Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of Japan between 1999 and 2001. Gaia is the only video game she worked on.

No comments:

Post a Comment